Tricontinental /Summary, April 16, 2024.

This dossier makes an X-ray of the Landless Rural Workers Movement (MST) and analyzes its forms of organization and struggle.

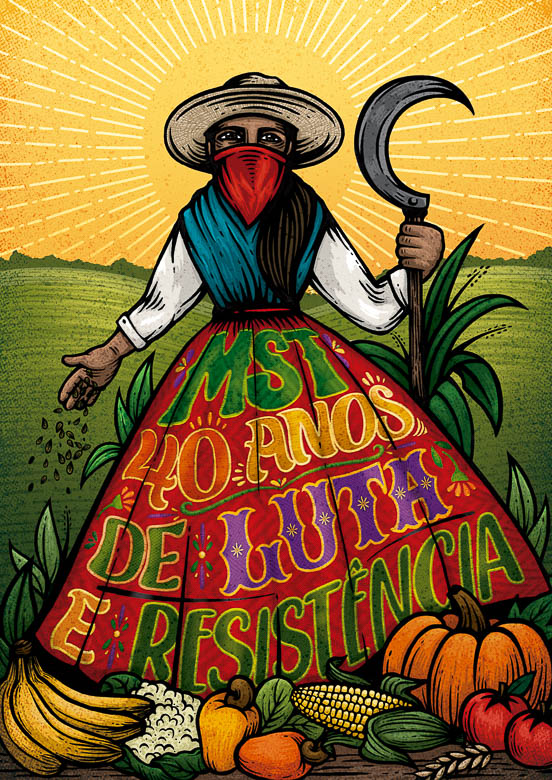

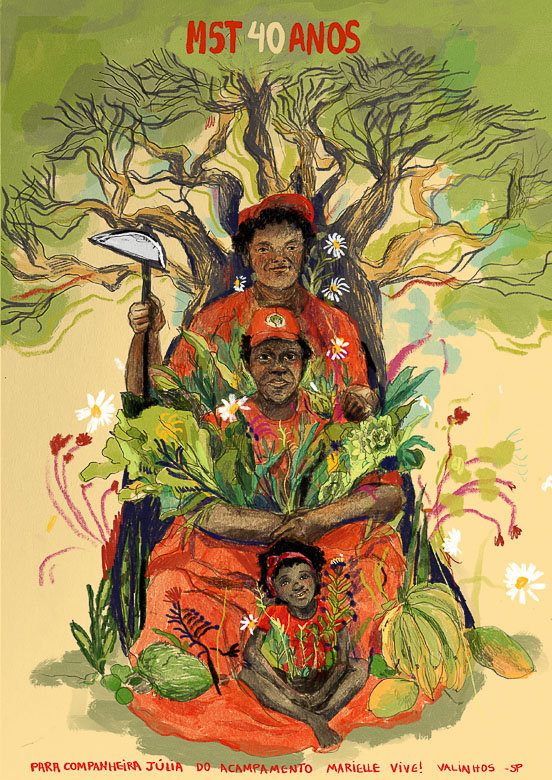

The works in this dossier are part of the 40-year MST

Art Convocation, organized by the Landless Movement, the Tricontinental

Institute for Social Research, ALBA Movements and the International

People's Assembly.

We want to thank the xs more than 150 artists

who presented themselves. Their contribution and solidarity with this

process further enriches and beautifies the struggle of the working

class, especially the peasant struggle, in addition to giving

reflections on the challenges ahead.

Artwork: Judy Duarte.Top

Introduction

In

September 1982, 30 rural workers and 22 pastoral agents met in Goiania,

the capital of the state of Goiás, in the central region of Brazil, at a

meeting organized by the Pastoral Commission of the Earth (CPT), an arm

of the Catholic Church inspired by Liberation Theology. These few

leaders represented the first peasant actions after 18 years of

repression of the peasant struggle by the business-military

dictatorship, which ruled the country for 21 years (1964-1985).

The

scenario was hopeful. The dictatorship languished in the face of the

economic failure and resurgence of mass struggles in the country,

especially a new trade union movement that would produce new leadership

and lead to the founding of the Workers' Party (PT) in 1980 and the One

Workers' Central (CUT), a vigorous unparalleled trade union center in

the history of Brazil, in 1983. Similar contexts were observed

throughout the Latin American and Caribbean continent: other military

dictatorships also aligned with the United States were dying, while the

struggle in Nicaragua and El Salvador inspired the Cuban Revolution in

previous years.

Peasants were still a dispersed force carrying out

local actions in a country of continental proportions, and faced, in

addition to political repression, the consequences of a forced

modernization of agriculture based on high mechanization, the intensive

use of agrotoxics and subsidies for large rural properties, which

stimulated the rural exodus. Even so, since 1979, there have been

occupations of large land properties in some states in isolation. Many

of them had the contribution and participation of the CPT. The meeting

in Goiaia discussed the future of these actions and, in the end,

indicated the need to build a movement of the peasantry, national and

autonomous, to fight for agrarian reform. It took another two years for

these joints to give rise to the foundation in 1984, in Cascavel, state

of Paraná, of the Movement of Landless Rural Workers of Brazil (MST).

This first meeting was attended by 92 leaders.

Twelve years later,

in 1996, the MST was already organized in all regions of the country,

had conquered land for thousands of families, its agrarian reform

settlements received the support and solidarity of other Brazilian and

international left-wing organizations, but it was still not considered a

relevant force in the political struggle, and was unknown to the

majority of the country's urban population. That year, however,

thousands of peasants marched in the direction of Belém, the capital of

the state of Pará, in the Amazon region, demanding an audience with the

then governor.

During the march, in Eldorado dos Carajás, in the

south of the state of Pará, they were surrounded by police forces and

gunmen hired by large companies in the region. At the head of the

protesters was Oziel Alves, a 19-year-old boy, with the responsibility

of keeping the spirit of his companions with slogans and motivation.

Oziel was one of the leaders identified by the police and separated from

the group. Before he was kneered, the police asked him to repeat, in

front of the weapons, which he said a few minutes earlier by the

microphone. Oziel did not hesitate, and his last words were: Long live

the MST.

Oziel was one of the 19 people killed in what is known as

the Eldorado Two Carajás Massacre. The days after the murders were

recorded by the internationally renowned Brazilian photographer,

Sebastian Salgado, gaining worldwide impact. The images, accompanied by

the music of the singer-songwriter Chico Buarque of Hollanda, and the

words of the writer José Saramago, crossed the planet in an exhibition

entitled Terra.

But it was

not the tragedy that made the MST recognised as a political force, but

its response to the crackdown. The following year, in February, in the

face of government impunity and the paralysis of agrarian reform, the

MST decided to start a march, with 1,300 people, starting from three

points from the country and arriving in Brasilia, the federal capital,

on April 17, 1997, exactly one year after the massacre of Eldorado dos

Carajás. At the time, the Agrarian Development Minister said that the

march, which traveled about 1,000 kilometers, would never reach

Brasilia. However, on the scheduled day, the and the Landless entered

the capital accompanied by 100,000 people, in what became the largest

political act against the neoliberal government of then President

Fernando Henrique Cardoso. This demonstration of strength and

organization has since made the MST one of the main protagonists of the

political struggle in Brazil (MST, "Sem Terras Marcham" country.

In

2005, the MST held a new national march. On that occasion, the

President of the Republic was Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, an old ally and

supporter of the struggle for agrarian reform. The march aimed to raise

awareness among the government about the changes brought about by the

financing of agriculture and demanding a new National Agrarian Reform

Plan.1

The

First National Agrarian Reform Plan was announced by the first civil

government after the business-military dictatorship in 1985, but was

never executed.Note at the foot

of May 2 to 17 May of that year, 15,000 people marched, a small moving

city that raised its tents every day in a new place of the tour, with

kitchens to feed, bathrooms, infrastructure for the nannies that

accompanied their mothers and fathers, and studies after the days of

marching. To ensure the organization of the ranks, a mobile radio

transmitter accompanied the march, and was heard by the 15,000 radios

carried by the peasants. After this march, the Brazilian Army invited

the MST to give a lecture at the Higher War College to understand how a

popular movement had such an organizational degree (MST, 2006).

Throughout

its four decades of existence, completed in 2024, the MST has achieved

some significant victories: 450 thousand families conquered land,

transformed into settlements of agrarian reform. These settlements,

where work can be individual or cooperative, have led to the creation of

185 cooperatives from local agricultural production cooperatives to

marketing cooperatives and the provision of services with regional scope

and 1,900 peasant associations. Part of the settlement is processed in

120 own agro-industries. In the camps, there are still 65,000 organized

families fighting for the legalization of land (MST, "Nossa Produ"o).

The

longevity of the MST is full of meaning. In all Brazilian history, no

peasant social movement has managed to survive even a decade against the

political, economic and military power of the big landowners. The

resilience of the MST has many components, such as the solidarity it has

received at the national and international levels. There are also

dimensions produced in the struggle that deserve further study, such as

the pedagogical proposal for education in the movement, political

formation, the organization of women, agroecological production and the

organization of cooperatives.

Among so many dimensions, the

Tricontinental Institute of Social Research chose the forms of

organization and struggle of the MST as the subject of this dossier.

Indeed, the strength of a popular movement comes from the number of

people it organizes and its method of organization. This is one of the

main explanations for how the Earthless Movement resists and grows in

the face of such an unequal correlation of forces. And this experience,

without pretending to offer formulas, but understood in the context of

the Brazilian struggle, can contribute to the reflections and

organizations of other popular and peasant movements around the world.

Artwork: Doubt Oliva.Top

The agrarian issue in Brazil

What

is now Brazil was founded and organized from the 16th century as a

capitalist company based on the great property of land, slave labor and

monoculture for export. The Portuguese colonial company caused a violent

rupture - by gunpowder and cross-size with the way of life of

indigenous societies, introducing a concept that did not make the

slightest sense for these communities: private property of nature's

common goods.2

Prior

to the arrival of the Portuguese, what is now Brazil was inhabited by

about 5 million people, divided into village communities, with community

dominance of the territory, dedicated to hunting, fishing, harvesting

and horticulture Maestri (2005).Nota al pie

In

1850, in the face of the eminent end of slavery due to abolitionist

movements and rebellions of the enslaved population, the then Brazilian

empire instituted the first Land Law to prevent the libertarians from

having access to the country's greatest source of wealth. By this law,

the land also became a commodity.

Moreover, this model called planting "monoculture slopes for export

based on the super-exploitation of the labor force" will be the only

constant in Brazilian history, regardless of sovereignty (Portuguese

colony or independent nation), the regime (monarchy or republic) and the

system of government (parliamentary or presidential).

Obviously,

in the face of this contradiction, the agrarian question has been at the

centre of rebellions, revolts and popular movements throughout the

country's history, from the indigenous resistance, the revolts against

slavery and the Quilombola communities 3

Of

the Quilombos, which are ancestral rural settlements with a majority

black population, initially created by escaped enslaved population. They

created their own form of organization and have rights similar to those

of indigenous territories.Nota al pie

The role of the State in defending the interests of landlords and

repression of the poor is also illustrative. While the indigenous and

enslaved populations were persecuted and fought by private militias, the

Brazilian Army itself tried to combat and eliminate the movements of

Canudos (1897), a self-managed community of 25,000 peasants, An armed

revolt of farmers to prevent an American railway company from taking

over its lands, and organizations fighting for agrarian reform before

the 1964 military-business coup, such as the Peasant Leagues.

As a

result, 21st-century Brazil continues to hold the second largest

concentration of land on the planet, a title it defended over the past

century, with 42.5% of properties under the control of less than 1% of

the owners (DIEESE, 2011). On the other side, 4.5 million peasants

considered landless.4

For a more detailed analysis of the agrarian issue in Brazil, see our dossier no. 27: https://thetricontinental.org/en/dossier-27-land/.Note to the foot

The class enemies of the landless are landowners, large landowners and transnational corporations that appropriate land for commodity

production. However, some of the pressure of the popular movement must

also be directed to the state. The current Brazilian Constitution was

approved in 1988, after the end of the business-military dictatorship,

and as it was built at a time of ascent of the mass struggles of people,

it incorporated many progressive aspects into its drafting, including

Agrarian Reform. Article 184 of the Federal Constitution provides that

agricultural property must fulfil a social function, must be productive

and respect labour and environmental rights. If they do not meet these

criteria, they can be expropriated for agrarian reform by the State,

responsible for compensating the owner or the owners and settling

landless families in these areas, which become public property.

The nature of the latifundio, however, has been transformed in recent decades according to the model of the so-called agribusiness.

The large unproductive and archaic property, used as a mechanism of

speculation, was incorporated by voluminous investments of international

financial capital, which controls sections of the rural production

chain, from seeds to the marketing of agro-industrial products. In 2016,

20 foreign groups controlled 2.7 million hectares in Brazil (Martins,

2020). This control accentuated monoculture for export, now converted

into commodities, large-scale

primary products marketed, with a unique global standard and used as

financial and speculative assets, negotiated on stock exchanges. In

Brazil in 2021, the obtaining of only five products, ear, corn, cotton,

sugar cane and livestock occupied 86% of any agricultural area and

represented 94% of all volume and 86% of the value of production (MST,

the Popular Agricultural Reform Programme). Agribusiness also depends on

the intensive use of agrotoxics, making the country the largest

consumer of agricultural poisons in the world, with a record consumption

of 130 thousand tons in 2023 (Spadotto and Gomes, 2021).

This

economic power is also expressed in political power. Agribusiness has

held ministerial positions in all Brazilian governments over the past

three decades. In the National Congress, Ruralist Banking, a supra-party

articulation of parliamentarians in defense of the interests of the

sector, brings together 324 federal deputies (61% of the House) and 50

senators (35% of the Senate) (FPA, 2023), sufficient power to impose

environmental and agrarian deregulation laws and to subject the MST to

inquiries in four Parliamentary Commissions of Inquiry (CPI) in two

decades. No other popular organization in Brazil's history has suffered

so many attempts at criminalization by Parliament. The first was created

during the first government of President Lula da Silva to force the

executive branch to reverse its relations with the Movement and prevent

public resources from being allocated to agrarian reform, in addition to

criminalizing the struggle for land. The last ICC, in 2023, had similar

objectives, again the new government of Lula da Silva was wanted, but

it had the opposite effect. The MPs who led the commission were part of

the most radical core of former President Jair Bolsonaro's government.

The MST, in turn, had expanded its public recognition from its

solidarity actions in the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, the ICC did

not gain political or media support, strengthened solidarity with the

Movement and did not even succeed in passing a final report.

Finally,

the hegemony of agribusiness in Brazilian society also combines the

sophisticated methods of a powerful cultural industry, from television

to music, with archaic methods of violence and repression. According to

the CPT's annual investigation into violence in the field,

in 2022 there were 2,018 incidents of social conflict in the

countryside, an increase of 33.6% over 2016, and 47 murders linked to

land or environmental issues (CPT, 2023).

In 1995, at its Third National Congress, the MST presented and approved for the first time its Agrarian Reform Program,

in which it presented its reading of the class struggle in the

Brazilian countryside and a set of proposals to transform the Brazilian

agrarian structure and living conditions in the rural area. In 2015, the

program was updated with a major theoretical and structural change:

while parties and universities mistakenly understood nature, and even

hailed the role of agribusiness in Brazil, the MST militancy

collectively built an interpretation that defined it as the presence of

transnational financial capital in the field for commodity

production. More than that, the MST pointed out that the existence of

agribusiness - and its ties with the State - disqualify a classic

agrarian reform, within the capitalist framework, of mere distribution

or democratization of access to land.

In this context, the MST was

forced to redefine its strategic actions and its agricultural

programme, formulating a new concept: the People's Agrarian Reform. In

addition to the distribution of land to peasants, the Popular Agrarian

Reform incorporates the need to produce healthy food for every

population, with a change of technological matrix towards agroecology

and the preservation of nature's common goods. This change also implies a

greater alliance with urban workers, the largest beneficiaries of

access to healthy and cheap food, as the Popular Agrarian Reform goes

beyond the interests of the peasantry to present itself as a policy for

every society, both for food sovereignty, as an alternative to

employment and income generation, and to combat the environmental

catastrophe.

Artwork: Wine. Top

Forms of struggle and awareness-building

The

MST was born with three objectives: to fight for land, that is, that

families organized in the Movement will conquer enough land to survive

their own work with dignity; to fight for popular agrarian reform, which

means to restructure the property and use of land; and to fight for the

transformation of society.

To achieve these objectives, the MST

was organized and defined from the outset as a mass movement, of a trade

union, popular and political character. A demass movement because it understands that the correlation of forces can only change in its favor by the number of people organized and, therefore, popular, because it is an organization open to the participation of all people who want to fight to work the land. The MST also combines trade union character, because the struggle for agrarian reform has its economic dimension and its real and immediate, but also political, because it knows that agrarian reform can only be achieved with a structural transformation of society.

In

addition, the MST is a national movement with performance in 24 of

Brazil's 26 states, which differentiates it from the movements that

preceded it, which had local and regional action, which made it easier

for them to be isolated by repressive forces. Being present in most of

the country, the MST can support the most difficult states and

nationalize local struggles, amplifying its impact.

In this way,

the consolidation and strength of the MST is due to the number of people

it organizes. In fact, even if it has multiple forms of organization,

according to each reality and place, the fundamental thing in the method

of organization is to put people in motion, in struggle. And through the struggle, develop their political and social consciousness.

The

Movement's first form of struggle is land occupations. Before or during

the occupation of an area, the MST organizes landless family camps.

These families meet identifying areas where peasants are concentrated

and organizing meetings, based on grassroots work that includes visits

to these people. From this moment on, families participate in the

organization of the future camp, looking for ways to get tarpaulins,

transport for families to carry out occupations, etc. In other words,

create the conditions for the occupation to come.

The camps have

the same role as the factories fulfilled in the formation of workers'

struggles in the 19th and 20th centuries. Gather the peasants in a

specific place, overcoming geographical isolation and allowing the

building of a sociability that serves as a basis for cooperation and

solidarity.

When they enter a camp, families are organized in

grassroots centres, groups of between 10 and 20 people. This small

number is established so that members can be known and prevented from

infiltrating unknown persons. In addition, divided into small groups,

more people can debate and express their views on the political

organization of the camp. In the cores, everyone has the right to use

the word, including nannies. In the camp, tasks must be organized and

distributed collectively: to search for water and firewood, to organize

food donations, to set up tents, to take care of security, to educate

children, etc. These tasks are organized in teams called sectors, made

up of members of the cores. I mean, every core has a participant in the

work teams. In this way, everyone participates in political life,

through debates, and in organizational life, through tasks. Always

collectively.

Regardless of the number of people participating,

meetings of the nuclei and sectors are always organized in advance, on a

well-defined agenda and always coordinated by a man and a woman. A

person has the task of registering decisions so that they are verified

by the core itself.

When discussions are related to decisions

across the camp, the views of the cores are taken to a coordination

space for the whole camp. If there is no consensus at that level, the

discussions return to the cores, with new ideas and questions, always

seeking to build synthesis and collective decisions.

In these

camps and in the occupations of land, assemblies are common to make

collective decisions, such as whether or not to occupy a latifundio,

whether or not they are retreating into a struggle. But this method of

assembly is only effective when all participants understand all the

dimensions of what is under discussion and the discussions are limited

to a few options, such as whether or not to make an occupation, whether

or not to resist eviction. For this reason, they are neither the main

nor the most common form of participation in the Movement.

When

the land is conquered, the occupation becomes a settlement of agrarian

reform and families remain organized in the Movement. This was one of

the first challenges of the Movement: how to keep families who had

already achieved some of their goals organized with the conquest of the

land? Part of the sociability and cooperation in the camp is lost in

this transition. That is why the Movement developed some mechanisms to

keep the people and those based on the move.

First,

years of life and struggle in camps produce an identity. The workers

organized by the MST are identified as No Earth (with capital letters).

That identity remains even after you have conquered the land. This

identity means sharing stories of struggles, identification with

families who remain camped and with values such as internationalism and

solidarity that are cultivated in struggles.

The organization of

the conquered territory brings new demands and struggles for rural

credit, education, health, culture, communication, etc. To achieve these

new demands, the MST maintains its organizational form. In other words,

families in the settlements are also organized in grassroots,

neighbourhood-based centres of between 10 and 20 members, with the

participation of all families. These nuclei again have a man and a woman

in coordination, the preparation of meetings, the registration of

decisions and also a flow of discussions and debates that goes from the

nuclei to coordination and vice versa. At each organizational level -

camp, settlement, region, state and national - a collective leadership

body is created.

The MST has and has never had a president or a

similar position that concentrated political decisions or differentiates

itself from the other militants. All the bodies of the Movement, from

the grassroots to the National Directorate, are collective and with two

years renewable. In this way, centralism and personalism are combated.

Related to this principle, there is the division of tasks: all people

must have responsibilities within the organization, to a greater or

lesser extent, so that there is neither excessive centralization nor

overload of militants.

Thus, in a camp or settlement there are

teams for daily tasks. The new demands are distributed among the

education, health, economic organization teams, among others. The more

complex the reality and the more the organization, the more teams are

trained, organizing in sectors at the state and national levels to plan

and execute more specialized tasks, such as production, mass front,

education, training, etc. For example, all educators or persons involved

in the education of the same region of municipalities form the

education sector, which prepares pedagogical proposals and participates

in the school life of the territories. In production, militants organize

economic life, cooperatives, as well as agroecological technology for

cultivation. And so on.

In these groups, the protagonisms of

subjects Without Earth are also recognized and integrated as the

collective of sexual dissents - something very rare in other peasant

organizations - and youth. Another form of participation is the

activities and meetings with the "sem terrinhas," the nannies of the

agrarian reform areas. In July 2018, the first National Encontro two Sem Terrinhas brought together more than a thousand boys and girls at a study camp, games and struggles in the federal capital, Brasilia.

Again,

the essential thing is to bring people together, create spaces for

collective discussion and move them through struggle and cooperation.

This means that, although land occupations are the presentation rate of

the MST, the movement combines different forms of struggle according to

the needs and conditions of each case. Within the repertoire of

mobilizations we also find marches - such as the major national marches

of 1997 and 2005 - the occupations of public buildings, roadblocks,

hunger strikes, etc.

It is practical action, the struggle, that

allows political consciousness not to fall asleep in camps or

settlements. For example, the MST has solidarity as one of its main

human and socialist values. But this is not only expressed in rhetoric

or speech. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, the Movement

donated more than a thousand tons of food in every country through the

organization of canteens, gardens and solidarity communities. Between

October and December 2023 alone, the MST sent 13 tons of food for

victims of Israeli attacks in the Gaza Strip (MST, 2023). The

organization of these actions requires discussions with families,

production planning, logistics organization, etc. In this process,

families know other realities, especially in urban areas, cooperate to

achieve their goals and experience these values in practice.

Another

mechanism may be the organization of cooperatives, where cooperation

takes place at work and distribution of surpluses, but also in the

organization of agro-dealities, concentrating people in common housing

centres, rather than rural isolation, and socializing domestic work,

with kitchens, dining rooms and collective nurseries.

Artwork: Nicolas Antunez.Top

Organizational principles of the MST

As

a national and mass movement, the MST assumes the autonomy of its

states, regions and territories. In this way, each group of organized

families, in settlements or camps, has the authority to make decisions

about their reality. However, unity

is essential for this mechanism to function autonomously and uniformly

in its organizational forms. This is possible because, since its

foundation in 1984, the Landless Movement has established some

organizational characteristics that have determined the very identity of

the Movement.

Organizational principles are the values, the form

of organization and the objectives by which a popular movement is

preparing to fight. They define the identity and unity of an

organization, while the suppression of one of them would alter the

nature of the organization. During the four decades since its founding,

these characteristics have not changed in essence, but they have been

radicalized to increase participation and raise the level of

consciousness of the mass movement.

One of the principles is

autonomy from political parties, churches, governments and other

institutions. The MST is autonomous from other organizations to define

its own political agenda. That doesn't mean the MST doesn't work with

political parties or religious organizations, of course, but it's a

fraternal relationship and not subordinate to them. Thus, the MST can

build a reading of reality, of the struggle for land and establish

tactics based on its own perception and the demands of organized

families.

As has been seen before, for the Movement to be popular and mass, it must have participation

as an organizational principle. This is also an example of how the

principle can be broadened, radicalizing its nature, but preserving its

essence. Initially, men occupied most of the coordination bodies.

Present in the struggle of the MST from the beginning, the organization

of women grew in various ways, but mainly in the Women's Collective.

They organized political training camps, direct actions against

transnational corporations, study spaces on gender relations and

capitalism, etc. This role broadened the principle of participation when

at the end of the 1990s, the Movement established that all leadership

and representation positions should be compulsorily occupied by a man

and a woman. This literally doubled the number of participants and went

on to correspond to the real weight of women in the organization. This

mechanism reinforced another principle: collective leadership.

For

the principles of collective participation and leadership to work,

discipline is necessary. For the MST, discipline means respecting

collective decisions, political lines and complying with them. There are

rarely any votes in the MST, and the most common thing is to agree on

decisions. When there is some difficulty in reaching consensus on an

issue, the debate returns to the cores of the grassroots and

coordination until the decisions are ripe and, then, once the line of

action has been defined, all the members of the Movement follow and

carry it out. Discipline is this compliance with collective decisions.

A

common feature of social movements is that they build their strategies

and tactics on the basis of their own practice. Without action and

practice, there is no popular movement. However, in order to permanently

analyse reality, the practice alone is insufficient. Therefore, another

organizational principle valued by the MST is the study.

This ranges from schooling, organizing families to fight for schools in

the areas of settlements and camps, such as the more than 2,000 public

schools conquered in areas of agrarian reform thanks to pressure on

local authorities, to the literacy of young people and adults, with more

than 50,000 people who have learned to read and write on the initiative

of the Movement or in collaboration with local governments (MST,

Education. Another dimension of the study is political training through

different processes - publication of books and booklets, study in the

cores of the basics, courses, etc. and which are in a way synthesized in

the experience of the Florestan Fernandes National School (ENFF), the

national political formation school of the Movement, which is part of

the set of the training schools of the International Assembly of

Peoples, a global articulation of popular organizations, social

movements, political parties and trade unions.

ENFF opened on January 23, 2005, and its name pays tribute to Brazilian sociologist and Marxist militant Florestan Fernandes.5

Committed

to the class struggle, he was one of the founders of the Workers' Party

and federal deputy in the elaboration of the Brazilian Constitution

after the business-military dictatorship.Note to the foot

The school has become an international reference for linking practice

with political theory. Throughout the year, militants, leaders and

cadres of popular organizations fighting for the construction of social

change in various countries study in classic in-depth national and

international political theory. Courses can last from one week to three

months, and are taught by volunteer teachers and intellectuals. ENFF

also offers training courses focused on various topics, such as

agrarian, Marxism, feminism and diversity. With teachers and students

from several countries, especially from Latin America, Florestan

Fernandes allows a cultural and political exchange between popular

movements, as well as a training on the global economic and social

landscape, always from the perspective of the working class (MST, 2020).

The

school was built literally by the hands of Landless workers across the

country, who organized into volunteer work brigades. The resources for

the construction were raised thanks to the solidarity work of

international support committees and the donation of the copyright of

Sebastian Salgado, Chico Buarque and José Saramago with the exhibition Terra.

In

addition to ENFF, the Movement has created other schools such as the

Joshua de Castro Institute of Education, which specializes in training

young managers for cooperatives, and agroecology schools, such as the

Latin American School of Agroecology (ELAA) and the Instituto Educar, in

the southern region of the country; the Popular School of Agroecology

and Agrofloresta Egídio Brunetto (EPAAEB), located in the northeast; and

the Institute of Latin American Agroecology (IALA), in the Amazon

region.

Part of the efforts to democratize access to knowledge

also materialized in the National Education for Agrarian Reform

Programme (PRONERA), a public policy conquered after the 1997 National

March. Through this program, the Brazilian government encourages the

creation of specific education courses, including bachelor's and

postgraduate courses, for landless workers. More than 100 agreements

have been signed with public universities that allow access to courses

in Agronomy, Veterinary, Nursing, teacher training, among many others.

In this way, the Movement occupies a traditionally elitist and

difficult-to-reach space, while forcing the academy to open its doors to

experience and knowledge produced in the heat of the struggle.

Another of the main values fed by the MST is internationalism,

understood as value and as a political strategy. Capitalism, as a world

system, establishes the entire planet as a battlefield and therefore

resistance must also be global. In addition to the articulations between

peasant movements, such as La Via Campesina and the Latin American

Coordination of Rural Organizations (CLOC) in Latin America, the MST

participates in other broader coordination spaces, such as ALBA

Movimientos and the International Assembly of Peoples.

However,

internationalism is not limited to spaces for international meetings and

meetings. As the principle and value of the organization, it has to

materialize in actions. From the simplest expressions of solidarity with

the peoples in struggle on the part of the families camped and settled,

to the construction of internationalist brigades, formed by militants

of the Movement to participate in exchange missions in the areas of

agroecology, production, education and training. Organized since 2006,

the Internationalist MST Brigades have been in Venezuela, Haiti, Cuba,

Honduras, El Salvador, Bolivia, Paraguay, Guatemala, East Timor, China,

Mozambique, South Africa and Zambia.

The oldest of them, the

Apollonian Brigade of Carvalho, whose name honors a Brazilian communist

militant who fought in the Spanish Civil War and the French Resistance,

acts in Venezuela supporting the political formation and dissemination

of agroecological techniques. The Jean-Jacques Dessalines Brigade in

Haiti has been acting in the same way since before the earthquake that

destroyed the country in 2010. In Zambia, in addition to agroecology,

the Samora Machel Brigade works on peasant literacy and, in Palestine,

every two years, the Ghassan Kanafani Brigade collaborates in the

harvest of olives in territories threatened by Israeli settlers.

Artwork: Fabrício Rangel.Top

The future of the struggle for land in Brazil

The

characteristics of the new MST Agrarian Program are given by the

contradictions and demands proper to the struggle in the countryside.

They give us guidance from what direction the struggle for land should

take, not only in Brazil, but throughout the Global South. Here we

highlight some of these dimensions and challenges.

The struggle for land is increasingly international.

The high concentration of income and land caused by financial capital

reduced control of the entire agricultural production chain to only 87

corporations based in 30 countries (Pina, 2018). These transnational

corporations threaten biodiversity and local cultures with their demands

for food standardization, set prices globally and interfere with

national legislation and rights. This means that peasant resistance will

also have to be increasingly international, with platforms and joint

actions, with pressure on multilateral organizations, but mainly by

fighting these transnationals in all territories.

The fight for land is a technological struggle.

Agribusiness is also defined by the massive diffusion of GMOs and the

intensive use of agrotoxics (pesticides and fertilizers). These

characteristics are inherent in the agribusiness itself. Without this

technological package, it is not possible to produce monocultures on a

global scale. That's why agribusiness, green or sustainable, is just

advertising. The overcoming of this model requires the strengthening and

massification of experiments in agroecology, the recovery of soils and

biodiversity, the appropriation and dissemination of new techniques and

technologies of production and environmental preservation, and the

national production of machinery, equipment and agricultural tools

suitable for the needs of the peasantry.

But it's not just about technology in agricultural production. As we describe in our dossier no 46, the technological giants and current challenges for the class struggle

(Tricontinental, 2021), mergers and concentration characteristic of the

movements of financial capital have brought together technology

companies, technology financiers and agribusiness companies to determine

the technological standard of the machinery and appropriate thousands

of data of nature, - imprisoned - in the cloud infrastructure controlled

by the Global North.

The struggle for land is a struggle for food.

The COVID-19 pandemic showed how transnational corporations took

advantage of the global crisis to inflate food prices and benefit from

speculation. But subjecting food to the logic of the financial market

also has other consequences, such as reducing the production of

traditional or local crops in favour of commodities commodities

with greater market acceptance. Growings such as soy, whose destination

is the production of fuel or animal feed (Tricontinental, 2019),

convert old food plantations into monoculture deserts. Added to this is

the risk of generating food crises by committing future crops on stock

exchanges. Even so, when agribusiness does not reduce production or

hinder access to food, it is producing poor quality food, rich in

agrotoxic waste.

The fight for land is an environmental struggle.

Agribusiness is one of those responsible for the climate and

environmental catastrophe, mainly due to large-scale deforestation to

replace forests with commodity

plantations or extensive livestock, which also emits large amounts of

carbon. In addition, the model of agribusiness expansion implies

excessive and deregulated consumption of water resources, the

disappearance of traditional plant and seed varieties, immediate

environmental impacts, such as the reduction of soil biodiversity, among

others.

The combination of the struggle for land and

environmental struggle also requires denouncing the false solutions of

green capitalism such as the carbon credit market. In this context, one

of the initiatives with practical and immediate effect at the national

level is the goal of planting 100 million trees in the coming years. In

its first four years, the Movement has already planted 25 million trees.

A

good example of how the MST combines environmental, technological and

food struggles is in the organization of the families based in the

metropolitan region of Porto Alegre, in the south of the country. This

is the largest production of agroecological rice in Latin America. There

are more than a thousand families that produce individually or in local

cooperatives, but all organized in a central cooperative, which

provides technical assistance and assumes the industrialization and

marketing of the product. Families are involved in both technical

management, responsible for agroecological supervision and

certification, and in economic and political management. The production

of agroecological rice has become a symbol of the large-scale productive

capacity of agroecology, the commitment of the MST to healthy food and

also solidarity, since large quantities of grains are often donated to

both urban community canteens in the region and to other countries.

The struggle for land is a cultural battle. The

consolidation of the hegemony of agribusiness is not only due to

economic and technological control, but also through the dissemination

of neoliberal values and the defense of the "modo de vida," of

agribusiness through countless mechanisms of the cultural industry, with

constant advertising on television, sponsorship and financing of the

media, organization of shows and financing of artists who literally sing

odas to the fund of monoculture. The construction of a

counter-hegemonic model of agriculture implies transformations in the

mode of agricultural production and in the social relations themselves

in the countryside, with agroecology, cooperation and study in

opposition to monoculture, individualism and ignorance.

On the

other hand, agroecology has also become an ally to convey the message of

a different agricultural model, by bringing together the environmental,

health, popular and scientific knowledge and diversity of popular

culture. The MST Culture Collective is an example of how this can

develop. This Collective works to produce and strengthen a culture of

its own, based on work fronts in literature, theatre and plastic arts,

and has played an important role in the relationship with society,

organizing the Festivals of Agrarian Reform in the states, a mixture of

food fair with cultural activities with MST musicians and supporters of

the struggle. These festivals reproduce locally the successful

experience of the National Agrarian Reform Fairs, held in Sao Paulo,

whose fourth and most recent edition in 2023, brought together more than

320 thousand people over four days.

Finally, the struggle for the land is part and depends on the struggle of the workers as a whole. The

peasantry alone does not have enough strength to face the large

transnational corporations that control agriculture. To defeat them, it

takes a powerful mass movement. In addition, the defeats of these

corporations and financial capital would open windows of opportunity for

a socialist project. In other words, since the present stage of

capitalism has elevated its characteristics to its maximum power, every

defeat inflicted on this model must and can necessarily be

anti-capitalist and therefore contribute, from the countryside or in

alliance with urban workers, to the construction of a project of human

emancipation.

Artwork: Natália Gregorini.Top

Notes

1

The First National Agrarian Reform Plan was announced by the first

civilian government after the business-military dictatorship in 1985,

but was never executed.

2

Before the arrival of the Portuguese, what is now Brazil was inhabited

by about 5 million people, divided into village communities, with

community dominance of the territory, dedicated to hunting, fishing,

harvesting and horticulture Maestri (2005).

3

of the Quilombos, which are ancestral rural settlements with a mostly

black population, initially created by escaped enslaved population. They

created their own form of organization and have rights similar to those

of indigenous territories.

4 For a more detailed analysis of the agrarian issue in Brazil, see our dossier no. 27: https://thetricontinental.org/en/en/dossier-27-land/.

5

Committed to the class struggle, he was one of the founders of the

Workers' Party and federal deputy in the elaboration of the Brazilian

Constitution after the business-military dictatorship.Arriba

Bibliographical references

Castro,

Mariana. MST completes 37 years and show a fora gives family farming

during pandemic. MST, January 22, 2021. Available at: https://mst.org.br/2021/01/22/mst-completa-37-anos-e-mostra-a-forca-da-agriculture-familiar-during-a-pandemia/.

Comisso Pastoral da Terra. Conflitos no country Brazil 2022. Goi?nia: CPT Nacional, 2023. Available at: https://www.cptnacional.org.br/downlods/download/41-conflitos-no-campo-brasil-publicacao/14302-livro-2022-v21-web.

DIEESE. Statistics do rural 2010-2011.

4.ed. Sao Paulo: Intersindical Department of Statistics and

Socioeconomic Studies, Nucleus de Estudos Agrários y Desenvolvimento

Rural y Ministério do Desenvolvimento Agrário, 2011.

Agropecuario Parliamentary Front. All you're sore, July 25, 2023. Available at: https://fpagropecuaria.org.br/alldos-os-membros/.

Instituto

Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE) Censo Agropecuário,

Florestal e Aquícola 2017. Retrieved on March 29, 2024. https://censoagro2017.ibge.gov.br.

Tricontinental Institute for Social Research. Complexo da Soja: Análise dos dice nacionais e internacionai s, 13 November 2019. Available at: https://thetricontinental.org/pt-pt/brasil/complexo-da-soja-analise-dos-dados-nacionais-e-internacionais/.

Not Dossier. 46. The tech giants and the current challenges to the class struggle. November 1, 2021. Available at: https://thetricontinental.org/en/dossier-46-gigantes-tech/.

Gramsci em del Movimiento de Rural Landless Workers (MST): an interview with Neuri Rossetto, Dossier does not. 54, 19 July 2022. Available at: https://thetricontinental.org/en/dossier-54-gramsci-mst-rossetto/.

Jakobskind, Mario Augusto. Stedile facestra palestra na Escola Superior de Guerra, July 19, 2006. Available at: https://mst.org.br/2006/07/19/stedile-faz-palestra-na-escola-superior-de-war/.

Maestri,

Mario. Absent Aldeia: indiums, caboclos, cativos, inhabitants and

imigrants na forma.o da classe Camponesa brasileira. In: Stedile, Joao

Pedro (ed.). A questo agrária no Brasil, volume 2 . O debate na esquerda 1960-1980. Sao Paulo: Expressáo Popular, 2005, pp. 217-276.

Martins, Adalberto. A Quest.o Agrária no Brasil, volume 10 . Da colánia ao governo Bolsonaro. Sao Paulo: Expressáo Popular, 2022.

- Organic rice and popular agria reform. Sao Paulo: Popular Express, 2019.

Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST). Sem Terras Marcham's hair Country. Available at: https://mst.org.br/nossa-history/97-99/.

Normas geris e Princípios Organizing. 2016.

It has been to Escola Nacional Florestan Fernandes, 15 years of training militants, January 24, 2020. Available at: https://mst.org.br/2020/01/24/conheca-a-escola-national-florestan-fernandes-ha-15-anos-formando-militants/.

In another donation, the MST sent 11 tons of food to families in Gaza, December 8, 2023. Available at: https://mst.org.br/2023/12/08/en-other-donacion-el-mst-envio-11-tons-from-food-a-las-familias-en-gaza/.

Educao. Retrieved 23 February 2024. https://mst.org.br/educacao/.

Nose Produ. Retrieved 23 February 2024: https://mst.org.br/nossa-producao/.

Program of Reform Popular Agriculture. 2024. Not published.

Pina, Rute. Only 87 companies control cadeia produtiva do agronegócio. Brazil of Fato, September 4, 2018. Available at: https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2018/09/04/so-87-enterprises-controlam-a-cadeia-produtiva-do-agronegoti.

Spadotto, Cláudio and Marco Antonio Ferreira Gomes. Agrotoxics not Brazil. Embrapa, December 22, 2021. Available at: https://www.embrapa.br/agencia-de-informacao-tecnologica/tematicas/agricultura-e-meio-environment/qualidade/ynamica/agrotoxicos-no-brasil:-text=Expresso%20quantidade%20de%20deredrediente,agr%C3%ADcola%20aumento%2078%25%20nesse%20per%C3%ADodo.

I'll

go, Lu. He has been to Escola Nacional Florestan Fernandes, 15 years of

age forming militants. MST, January 24, 2020. Available at: https://mst.org.br/2020/01/24/conheca-a-escola-national-florestan-fernandes-ha-15-anos-formando-militants/.

[La pedagogía crítica y la lucha anti-fascista]....,

[La pedagogía crítica y la lucha anti-fascista]...., Israel

creyó que podría lanzar un golpe contra Irán sin sufrir consecuencias.

Esto ya se acabó, pese a que Irán en forma deliberada no infligió una

acción extremadamente letal

Israel

creyó que podría lanzar un golpe contra Irán sin sufrir consecuencias.

Esto ya se acabó, pese a que Irán en forma deliberada no infligió una

acción extremadamente letal

En

regiones diferentes del mundo, esos altísimos gastos están al servicio

de una misma estrategia, la estrategia de dominación global de los

anglosajones.....,

En

regiones diferentes del mundo, esos altísimos gastos están al servicio

de una misma estrategia, la estrategia de dominación global de los

anglosajones....., El

economista marxista argentino va a fondo en el análisis geopolítico, la

crítica a los progresismos y la caracterización de las nuevas

ultraderechas....,

El

economista marxista argentino va a fondo en el análisis geopolítico, la

crítica a los progresismos y la caracterización de las nuevas

ultraderechas....,

You must be logged in to post a comment Login